The growth of an economy, regardless of the measure used, is the ultimate goal of government policy. It follows logic that, if an economy grows, then the population will be engaged in income-generating activities and live decent lives with access to healthcare, humane sanitation, food, education, and social freedoms.

One major component and driver of economic growth is a functioning financial system. A little background will help form the basis of our latter discussion. In any country or economic system, you have two main players; those that have excess money i.e. money over and above their needs, and those that don’t have money for additional expenditure. The formal terms for these are savers and borrowers. These groups of people run into thousands or even millions in a given country. This presents a serious problem in an economy:

- How does a borrower find a saver?

- How does the saver trust that the borrower will pay back?

- How does the borrower find enough savers to lend to him?

- How do the two or more parties agree on what would be fair compensation?

- How does the borrower find savers willing to lend at the tenor they need the money for?

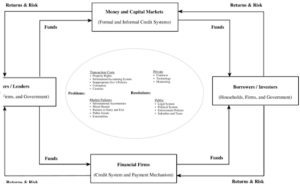

The problems above are not exhaustive but paint a basic picture of why a financial system is needed. In basic terms, a financial system is a system that aggregates savings and can match the needs of borrowers and savers. Without a functioning financial system, businesses and entrepreneurs would not get money to invest in their new ideas and expand while savers would not earn on their savings leading to no economic growth.

A financial system has several players including banks, stockbrokers, stock exchanges, insurance companies, fund managers, borrowers, and lenders who all interact to make the above questions answerable as shown in the diagram below.

The hallmarks of a financial system could then be summarised as:

- Ability to aggregate savings

- Ability to transform savings into loans

- Ability to manage duration risk

- Ability to price

The two largest components of the financial system are capital markets and money markets. The difference between the two is that money markets primarily match short-term excess money to short-term borrowers while capital markets match long-term excess money with long-term borrowers. Both of them have to exhibit the hallmarks summarised above.

There are times when a local financial system does not have enough savers to meet the demand of borrowers either in the quantum amounts needed, risk, or duration. It, therefore, has to open up to money flows and into excess savers from outside its ecosystem.

Looking at Africa financial systems, especially the capital markets, there are two main questions:

- Is it a lack of savings or a lack of innovation by the players?

- Are the capital markets structured for the typical African economy?

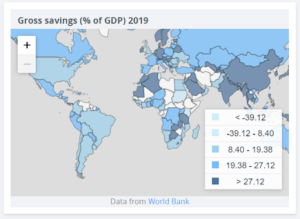

Africa’s average saving rate to GDP is 18%.

An examination of a cross-section of African countries from the data seems to show that Africa generally does not have a saving problem. For example, Zambia’s saving rate is 40%, Algeria’s is 38%, and Nigeria’s is 22%. Some countries have low saving rates like Kenya’s 8%.

From the above, we can say that saving is not a major issue. Failure to aggregate savings in a manner that meets demand seems to be the biggest problem. This statement reduces our two questions above to a single statement problem.

The largest aggregator of savings in the continent is the banking sector. However, on average, around 66% of the bankable population is not banked. The large saving rates seen above arise from people saving in informal circles like chama’s in Kenya, Stokvel in South Africa, and Ajo’s in Nigeria. This shows that there is a huge lack of affordable aggregating vehicles such as Collective Investment Schemes to tap into this pool. As long as these savings are out of the formal financial system, they are not aggregated. The borrowers’ needs can therefore not be met leading to an artificial deficit in the local financial system.

Africa can be defined by its predominantly informal economy and a majority of its people being based in rural areas. This presents an opportunity for low-cost digital penetration to these people that offers, not only transaction mechanisms such as mobile money (MPESA) but also formal banking accounts for longer-term saving. Banks should then use their trust factor to introduce mutual fund-like products for the low income persons to tap into the large pool of informal savings in a Stokvel or Chama-like fashion i.e banking groups digitally.

Without innovative aggregation of savings, there will be no deposit transformation to meet the local demand for capital without opening up the local financial system to inflows from excess savings from outside.

Assuming that the aggregation of savings problems are surmounted, we remain with one more question: are the capital markets structured for Africa? For this, I would answer NO. Do we have functional capital markets in Africa? Yes, but functional by whose definition? We define functional when an investor can come in to buy their equities or debt instruments, make their return, and go (in the case of a foreigner, repatriate their funds). However, the correct definition is, the main role of a capital market is to be able to transform aggregated savings into solutions or products for the sector that needs those savings to apply them into new ideas or expand existing ones.

Capital markets are a tool that should lead to growth of private enterprise. However, in Africa they seem not to play that role. Why? Because of this unique feature that, on average 80% of Africa’s economy is MSME to SME. The major need for this sector is patient, long-term capital which, unfortunately, is not catered for with the right solution by the largest aggregator of savings on the continent.

If players in the African capital markets are not able to transform the aggregated savings into long-term, patient capital, then the capital markets fail their primary role of being a driver of economic growth. One major concern for aggregated saving vehicles (using this instead of providers of capital as it is not their capital) is the risk of MSMEs or SMEs. True MSMEs do need capacity building and access to markets as key ingredients for their growth. However, through digital innovation, aggregators of savings can use fund of funds structures and crowdfunding structures which effectively disaggregate concentration risk, credit risk, and liquidity risk.

The challenge presented is how players in the African capital markets can effectively and efficiently aggregate savings and transform them to the needs of the demand as presented by the MSME and SME space.